Jean-Pierre Pincemin at Denise Cade, New York, NY.-Review of Exhibitions-

Brief Article by Barbara Rose:

Jean-Pierre Pincemin was born in Pads at the end of World War II. At 16 he was working on the assembly line in the Renault factory producing the Concorde engine prototype. He attended neither art school nor college. In France, Pincemin is somewhat known, but as an unpredictable “outsider,” an eccentric loner, a politically incorrect, unreconstructed Trotskyist who never bought the Maoist line when it was trendy. A jazz enthusiast who publishes poetry, he has steadfastly refused to participate in the trivial pursuits of Parisian vie mondaine or the hollow rhetoric of post-structuralist obscurantism. Instead he has pursued a uniquely rigorous line of investigation defining the limits of modernist painting.

Among the founders of the Support/Surface group, who constitute the only substantial postwar effort to drag the School of Pads back into the front ranks of the international avant-garde, Pincemin has kept up as no other French artist with developments in the big world beyond the Eiffel Tower. His recent show at Denise Cade provided an opportunity to see what he has been up to recently. Practical considerations determined that most of the paintings shown were medium and small size. This is too bad, because Pincemin is at his best on a large scale that gives full play to the force of his imagery and the nuances of his style.

I say style, but it is part of Pincemin’s subversive impulse to undermine conventional concepts, including that of personal style as an expression of subjective authenticity. Unquestionably, Pincemin is perverse. However, his perverseness, which results in shifting emphasis and redefining premises, permits an incredibly creative originality. Contrariness led him to take the canvas off the stretcher in his Support/Surface salad days, and later to begin making bizarre neo-Constructivist sculpture. Made out of the leftovers of gutted slum buildings and lashed together with primitive wiring, it looks dirty and dilapidated instead of utopian. There is a message in these materials and techniques: even the small sculptures would look awful on your marble coffee table.

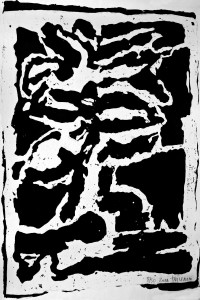

Pincemin’s dialectical contradictoriness is apparent in his dedication to nonreproducibility in his recent paintings. Mostly he uses close-valued colors that eliminate the kind of high contrast required for reproduction impact. But Pincemin’s effort is to define painting in opposition to the slickness and uniform surfaces of photography or printed reproduction. Like Gerhard Richter and Robert Morris, Pincemin demands the freedom to work simultaneously in two styles, one abstract and one representational, a practice which creates trademark identification difficulties. Both styles were represented in the recent New York show. It takes knowledge of Pincemin’s sources, however, to realize that what his two modes have in common is holistic imagery and religious iconography. Pincemin’s images, which range from human figures and wild animals to abstract forms resembling mandalas, are taken from Eastern and Western religious texts — Persian miniatures, Buddhist cosmogonies, Biblical subjects as seen by medieval printmakers.

Pincemin accepts as a point of departure that advanced painting since Newman rejects Cubist rhyming and identifies a single image with the whole of the field. However, he turns away from Newman’s single, saturated-hue fields back in the direction of Newman’s source, Matisse. Then he turns away from Matisse’s languid brushstroke and relatively uniform surface texture back in the direction of Cezanne’s sculptural and constructive, palette-knifed, not just visible but physical brushstroke. Taking this argument regarding the priority of the stroke further, he exposes previous layers of the paintings in an updated version of Cezanne’s non finito, leaving the canvas bare at the framing edges. This frangible, peeling and detached surface proclaims flatness in its revelation of the literally material underpainted pigment as much as his unstretched canvas ever did.

Like no other country, France lives and dies by the cultural agenda of its elite. At present that ruling elite has so lost respect for its own culture that it has displaced the marginal to the center and in so doing robbed itself of what once made it great — a rationalism humanized by sensuality, a refinement leavened by physicality, a vigor that requires self-criticism and doubt. Bad conscience about the horrors of French colonial imperialism produces an awe for all that is autre. The School of Pads is not dead, it is just not where the French ruling class is looking for it. Pincemin is one of the three living School of Paris painters (the other two are Francois Rouan and Georges Noel) sure to last beyond the current modish moment. Pincemin thoroughly reinterprets both painting and its content and in so doing gives it a temporary new lease on life. How could it be, then, that he has not had a major full-scale retrospective?